2018

Convergence

Catalogue essay by Dr Sheridan Coleman

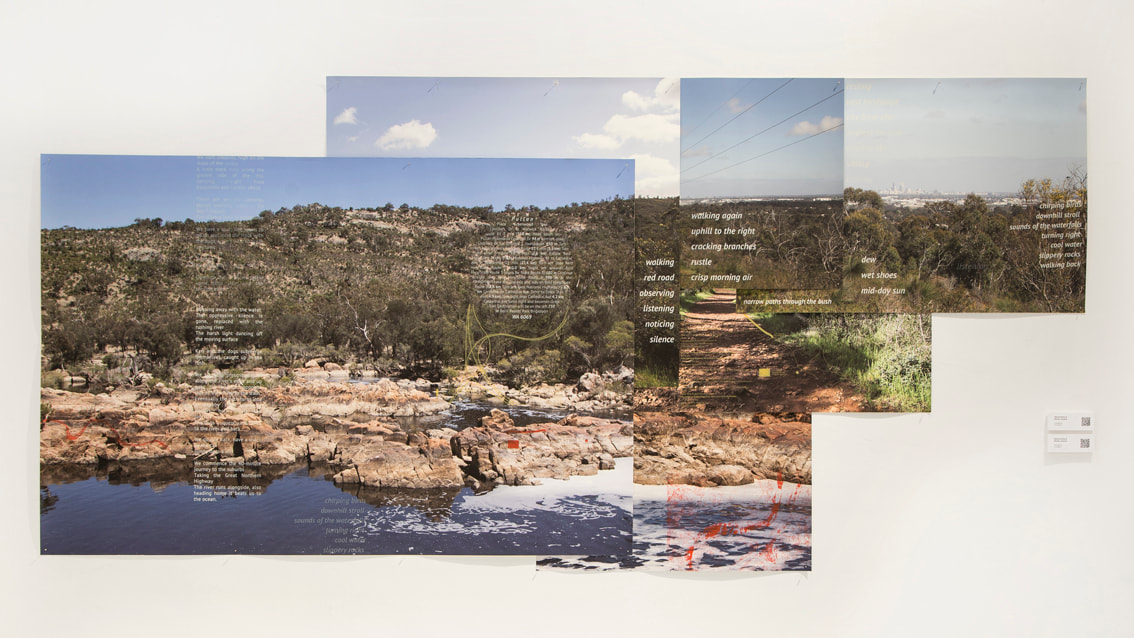

On a winter morning in July, a well-noted fortnight of rain over Perth lifted. The mild sunshine brought on a modest wanderlust in printmaker Melanie McKee. She determined to be, presently, amidst the damp, mid-year greening of the bush. With her husband, dogs and camera, McKee followed GPS prompts to a gravel car park, skirted some eerie railway surveillance cameras, and crossed a park footbridge into a superlative ether of light and sensation.

Water glittered and gurgled. The air was temperate, suffused with sunlight and stippled with Sunday noises: the pock of bocce played on dry grass, the hollow scrape of a landing kayak, hissing sausages, pebbles grumbling underfoot. It was the sort of day you can’t wait to remember, even while standing in it.

Bells Rapids Park lies on the perimeter of Perth, Western Australia, where the flat metropolis is encircled by Darling Scarp, or ‘The Hills’. It’s a dualistic colloquialism: “somewhere in the hills” means far away, but travelling “to the hills and back” is a breezy day out. For McKee, this short distance delivered her to undeveloped bushland, and that most delightful sensation of being in an interlude.

Nearby, acting on a similar climactic opportunity, Monika Lukowska pulled into Lesmurdie Falls in Mundy Regional Park. Signposts graded the difficulty of various trails. Nobody was around. Trepidation stirred. Was it warm enough for Dugites? Did anybody know where she was? Lukowska pressed forward into Marri and Jarrah woodland.Worry dissipated with each step, giving way to curiosity, then appreciation, then ease.

Walking engages our sensory appetites, feeding the eye with a cascade of approaching observations.At first we notice colour, sky, elevation.With more walking, these broad strokes erupt into a cacophony of finer details: gutters of fluorescent Sourgrass, Magpies warbling, foam cycling in the rapids, the brassy, lemon-and-oil scent of Eucalypts, the graphite gloss of a Skink’s back, the tannic river water, its flickering Pinnaroo Fish.You exhale.Walking rinses you.

Back in the studio, McKee and Lukowska began a process of purposeful remembering and layering.They talked, compared photographs, found maps and prepared screens. They worked through concepts like ‘semblance’, ‘atmosphere’, ‘making place’ and ‘cadence’. They noticed little patterns: rivers sluiced both parks; one’s on a hill, the other’s in a valley; one lay beside a commercial railway; the other beneath aeroplanes descending into Perth International. These thoughts were narrative eddies, poetic shapes without specific messages, but which testified to a state of being awake and available to one’s surroundings.

The artists did not endeavour, after historic landscape tradition, to ‘capture’ the landscape. Rather, they looked to begin a relationship: with two parks, with Perth, with place.This is because McKee and Lukowska are coming at this project from the same direction, which is to say, from two different places outside of Australia. McKee was born in Zimbabwe and moved to Perth in 2001. Lukowska relocated from Poland. Both artists put down roots, studying and working in Perth’s sprawling coastal suburbs.Their collaboration arises from a mutual commitment to remembrance and exploration, in a long, ongoing transition between feeling at home in one place and feeling at home in another.

Pruned from McKee and Lukowska’s approach are any typical plots of landscape art: they have no ecological or political agenda; they don’t seek archetypal or revolutionary experiences of nature; nor do they acknowledge the possibility of an endpoint, of completely knowing a place.Their activities – walking, documenting, research, discussion – are both autobiographical and artistic. This open, attitudinal methodology helps them unite everywhere they remember with new experiences and place making efforts, in one continuous biography.

All this collaborative thinking and feeling is manifest in Convergence. Its layers tell of the slipperiness and compounding of memory. Its wayfinding symbols map out the principles and poetics of visiting, for future forays.The print’s saturation refers both to Perth’s azure sky and iron-red earth and the amplification of these trips in each artist’s memory. If Convergence makes you linger on some past, sun-soaked day in the countryside, it is because this work invites the celebration of any modest or light-hearted endeavour to escape from routine and begin a full and open encounter with place.

Convergence

Catalogue essay by Dr Sheridan Coleman

On a winter morning in July, a well-noted fortnight of rain over Perth lifted. The mild sunshine brought on a modest wanderlust in printmaker Melanie McKee. She determined to be, presently, amidst the damp, mid-year greening of the bush. With her husband, dogs and camera, McKee followed GPS prompts to a gravel car park, skirted some eerie railway surveillance cameras, and crossed a park footbridge into a superlative ether of light and sensation.

Water glittered and gurgled. The air was temperate, suffused with sunlight and stippled with Sunday noises: the pock of bocce played on dry grass, the hollow scrape of a landing kayak, hissing sausages, pebbles grumbling underfoot. It was the sort of day you can’t wait to remember, even while standing in it.

Bells Rapids Park lies on the perimeter of Perth, Western Australia, where the flat metropolis is encircled by Darling Scarp, or ‘The Hills’. It’s a dualistic colloquialism: “somewhere in the hills” means far away, but travelling “to the hills and back” is a breezy day out. For McKee, this short distance delivered her to undeveloped bushland, and that most delightful sensation of being in an interlude.

Nearby, acting on a similar climactic opportunity, Monika Lukowska pulled into Lesmurdie Falls in Mundy Regional Park. Signposts graded the difficulty of various trails. Nobody was around. Trepidation stirred. Was it warm enough for Dugites? Did anybody know where she was? Lukowska pressed forward into Marri and Jarrah woodland.Worry dissipated with each step, giving way to curiosity, then appreciation, then ease.

Walking engages our sensory appetites, feeding the eye with a cascade of approaching observations.At first we notice colour, sky, elevation.With more walking, these broad strokes erupt into a cacophony of finer details: gutters of fluorescent Sourgrass, Magpies warbling, foam cycling in the rapids, the brassy, lemon-and-oil scent of Eucalypts, the graphite gloss of a Skink’s back, the tannic river water, its flickering Pinnaroo Fish.You exhale.Walking rinses you.

Back in the studio, McKee and Lukowska began a process of purposeful remembering and layering.They talked, compared photographs, found maps and prepared screens. They worked through concepts like ‘semblance’, ‘atmosphere’, ‘making place’ and ‘cadence’. They noticed little patterns: rivers sluiced both parks; one’s on a hill, the other’s in a valley; one lay beside a commercial railway; the other beneath aeroplanes descending into Perth International. These thoughts were narrative eddies, poetic shapes without specific messages, but which testified to a state of being awake and available to one’s surroundings.

The artists did not endeavour, after historic landscape tradition, to ‘capture’ the landscape. Rather, they looked to begin a relationship: with two parks, with Perth, with place.This is because McKee and Lukowska are coming at this project from the same direction, which is to say, from two different places outside of Australia. McKee was born in Zimbabwe and moved to Perth in 2001. Lukowska relocated from Poland. Both artists put down roots, studying and working in Perth’s sprawling coastal suburbs.Their collaboration arises from a mutual commitment to remembrance and exploration, in a long, ongoing transition between feeling at home in one place and feeling at home in another.

Pruned from McKee and Lukowska’s approach are any typical plots of landscape art: they have no ecological or political agenda; they don’t seek archetypal or revolutionary experiences of nature; nor do they acknowledge the possibility of an endpoint, of completely knowing a place.Their activities – walking, documenting, research, discussion – are both autobiographical and artistic. This open, attitudinal methodology helps them unite everywhere they remember with new experiences and place making efforts, in one continuous biography.

All this collaborative thinking and feeling is manifest in Convergence. Its layers tell of the slipperiness and compounding of memory. Its wayfinding symbols map out the principles and poetics of visiting, for future forays.The print’s saturation refers both to Perth’s azure sky and iron-red earth and the amplification of these trips in each artist’s memory. If Convergence makes you linger on some past, sun-soaked day in the countryside, it is because this work invites the celebration of any modest or light-hearted endeavour to escape from routine and begin a full and open encounter with place.

2017

Emplacement

Catalogue essay for Locale, by Dr Sheridan Coleman

Beneath the towering eucalypts of Beeliar country, and among the stately former dormitories of Point Heathcote Reception Home, seven artists gather to compare their understandings of ‘place’. From this natural lookout, they picture homes, neighbourhoods and imagined spaces, before returning their gaze to Heathcote, where their prints hang within the site’s history.

Place, as it unfolds in Locale, does not simply mean ‘location’. Rather, it indicates a state of involvement with site. It describes the imaginative work by which each artist has shaped or come to understand specific places. With this in mind, each print is a place in its own right, a surface upon which the evidence of labour has accrued: sewing, scanning, remembering, etching, walking.

The ‘home’ is where place coincides with belonging. While Melanie McKee focussed on her long-haul PhD study, her home shifted into utility mode: it became studio, office, library; an eating and sleeping station. Linen prints depict these cloistered spaces at dawn, before the day ahead feels plausible. Mild regret (the Mel of yesterday has left dishes for today’s Mel to tidy) mingles with gratitude for the nourishment of home. By slowly and repetitively sewing through her prints, McKee lingers and repays some of “the debt owed” to the place that supports her work.

Each day, Layli Rakhsha rises with her daughters at a crisp 5:30am. Each night, quiet descends at 7:30pm, when the house becomes hers alone. Rakhsha prepares for this hour by gently and meditatively ordering her space: straightening carpets, clearing the table, readying tomorrow’s fruit. This silent ritual transforms a functional room into a space for reflection, nostalgia, joy and selfhood, recorded in seven prints, judiciously tinted with black. Domestic minutiae, Rakhsha seems to whisper, are not inconsequential, but kindle quietude and comfort.

In a former cell, Gemma Weston remembers the private enterprises of the teen bedroom. Drypoints of Smash Hits coverboys, a sumptuous ‘crazy quilt’ and a scented, bobby-socked bedhead describe how personhood can be shaped by place-making activities, here crafting and customisation. Weston’s powerful evocations revivify and invite humility for our former, less certain selves. Monitored by parents and unresourced, the extent of bedroom self-determination was modest, yet this space was everything, a private gallery, a duchy. For McKee, Weston and Rakhsha, place is not always physical, but can exist in remembrance, invoked through ritualised artistic labour.

At a larger scale, place is shaped communally. Neighbourhoods and suburbs incorporate gardening fashions, transportation networks, governance and community culture. Emma Jolley, a Northern Suburbs native, and Monika Lukowska, a native of three years, have forged individual paths through collective place. Jolley portrays the trappings of suburban idealism according to her knowledge of its history, eulogising the decommissioning of kidney-pools and frangipani in favour of gentrification and grey render. Lukowska compares Perth’s suburbs with her industrial, mountain-encircled hometown in Poland. She provokes her new surroundings to reveal their secrets and history with extensive walks. The prints of both artists are spacious. Jolley charts sprawl as the manifestation of Perth’s instinct towards open space and Lukowska’s filmy lithographs look over the treeline toward an expansive sky that goes on and on no matter how far she walks.

Locale imports diverse accounts of place into Heathcote. In this way, it echoes The Log, Heathcote Hospital’s long out-of-print quarterly journal, which published outside artists and writers alongside patients and staff. Carly Lynch disinterred several issues of The Log from a literal (and figurative) archival basement, and assiduously copied their faded pages to fabricate fresh issues. Her labour has reinstituted the readability of these previously untouchable archival documents. She has also reinstituted their raison d’être: to meaningfully connect this sun-kissed promontory with the world outside.

The Log has also spoken across time: through this project, Rachel Salmon-Lomas (Riley) discovered that her father was once resident chaplain at Heathcote Hospital. Riley scanned The Log for evidence of his work, receiving and assuaging the worries of patients. Serendipitously returned to this site of institutional and family history, Riley interprets her father’s profoundly spiritual connection to this place. The rainbow-lipped black hole on his hand-latched rug seems symbolic of some kind of time slip, by which Riley may hang her work beside his, sharing this place and moment together.

Place, as these seven artists describe it, is not a rigid physical site, but something that can be modified, created, demolished, remembered or imagined. In Locale, it is the “pain, joy and time” of printmaking (as Rakhsha puts it) through which each artist has found and made place.

Sheridan Coleman

Emplacement

Catalogue essay for Locale, by Dr Sheridan Coleman

Beneath the towering eucalypts of Beeliar country, and among the stately former dormitories of Point Heathcote Reception Home, seven artists gather to compare their understandings of ‘place’. From this natural lookout, they picture homes, neighbourhoods and imagined spaces, before returning their gaze to Heathcote, where their prints hang within the site’s history.

Place, as it unfolds in Locale, does not simply mean ‘location’. Rather, it indicates a state of involvement with site. It describes the imaginative work by which each artist has shaped or come to understand specific places. With this in mind, each print is a place in its own right, a surface upon which the evidence of labour has accrued: sewing, scanning, remembering, etching, walking.

The ‘home’ is where place coincides with belonging. While Melanie McKee focussed on her long-haul PhD study, her home shifted into utility mode: it became studio, office, library; an eating and sleeping station. Linen prints depict these cloistered spaces at dawn, before the day ahead feels plausible. Mild regret (the Mel of yesterday has left dishes for today’s Mel to tidy) mingles with gratitude for the nourishment of home. By slowly and repetitively sewing through her prints, McKee lingers and repays some of “the debt owed” to the place that supports her work.

Each day, Layli Rakhsha rises with her daughters at a crisp 5:30am. Each night, quiet descends at 7:30pm, when the house becomes hers alone. Rakhsha prepares for this hour by gently and meditatively ordering her space: straightening carpets, clearing the table, readying tomorrow’s fruit. This silent ritual transforms a functional room into a space for reflection, nostalgia, joy and selfhood, recorded in seven prints, judiciously tinted with black. Domestic minutiae, Rakhsha seems to whisper, are not inconsequential, but kindle quietude and comfort.

In a former cell, Gemma Weston remembers the private enterprises of the teen bedroom. Drypoints of Smash Hits coverboys, a sumptuous ‘crazy quilt’ and a scented, bobby-socked bedhead describe how personhood can be shaped by place-making activities, here crafting and customisation. Weston’s powerful evocations revivify and invite humility for our former, less certain selves. Monitored by parents and unresourced, the extent of bedroom self-determination was modest, yet this space was everything, a private gallery, a duchy. For McKee, Weston and Rakhsha, place is not always physical, but can exist in remembrance, invoked through ritualised artistic labour.

At a larger scale, place is shaped communally. Neighbourhoods and suburbs incorporate gardening fashions, transportation networks, governance and community culture. Emma Jolley, a Northern Suburbs native, and Monika Lukowska, a native of three years, have forged individual paths through collective place. Jolley portrays the trappings of suburban idealism according to her knowledge of its history, eulogising the decommissioning of kidney-pools and frangipani in favour of gentrification and grey render. Lukowska compares Perth’s suburbs with her industrial, mountain-encircled hometown in Poland. She provokes her new surroundings to reveal their secrets and history with extensive walks. The prints of both artists are spacious. Jolley charts sprawl as the manifestation of Perth’s instinct towards open space and Lukowska’s filmy lithographs look over the treeline toward an expansive sky that goes on and on no matter how far she walks.

Locale imports diverse accounts of place into Heathcote. In this way, it echoes The Log, Heathcote Hospital’s long out-of-print quarterly journal, which published outside artists and writers alongside patients and staff. Carly Lynch disinterred several issues of The Log from a literal (and figurative) archival basement, and assiduously copied their faded pages to fabricate fresh issues. Her labour has reinstituted the readability of these previously untouchable archival documents. She has also reinstituted their raison d’être: to meaningfully connect this sun-kissed promontory with the world outside.

The Log has also spoken across time: through this project, Rachel Salmon-Lomas (Riley) discovered that her father was once resident chaplain at Heathcote Hospital. Riley scanned The Log for evidence of his work, receiving and assuaging the worries of patients. Serendipitously returned to this site of institutional and family history, Riley interprets her father’s profoundly spiritual connection to this place. The rainbow-lipped black hole on his hand-latched rug seems symbolic of some kind of time slip, by which Riley may hang her work beside his, sharing this place and moment together.

Place, as these seven artists describe it, is not a rigid physical site, but something that can be modified, created, demolished, remembered or imagined. In Locale, it is the “pain, joy and time” of printmaking (as Rakhsha puts it) through which each artist has found and made place.

Sheridan Coleman

2016

TERMINUS in search of an (im)possible conclusion

Catalogue Essay by Dr Ann Schilo

A terminus is a place of arrival and departure - an airport concourse, a train station, bus depot, a port-of-call that is often the end point of a journey. As travellers, wayfarers, strangers or welcomers, we have all been there, physically and emotionally drawn into its machinations. As a physical location, the terminus is a noisy place of transit. Marc Auge (1995) contends such spaces are 'non-places'. They are zones of mobility whose architectural forms and configurations present a generic view of the world, a nowhere but everywhere that people pass through on their way to somewhere. For many migrants and refugees, the terminus is not just a physical place of embarkation but a metaphoric location. It can be both an ending and a beginning, offering incalculable moments of transition and possibility as the memories of the past succumb to the cacophonous dreams and desires for the future.

Having arrived here from elsewhere, both Melanie McKee and Monika Lukowska imagine Perth as a kind of terminus. Yet unlike Auge's contention that it is a generic 'non-place', they picture its unique characteristics as a location of affective and embodied sensibilities. Drawing upon their experiences of residing in differing locales, they render the paradoxical senses of dislocation and belonging as they try to become emplaced. Individually and in collaboration, they mobilise their artistic expertise to respond to the specificities of living here, in this place, as it tugs at their memories, emotions and desires. Thus this exhibition offers an appreciation of the affective dimensions of emplacement and the material conditions of knowing our place in the world through the practices of two women artists as they picture their (im)possible terminus.

Melanie McKee whose family migrated here after being dispossessed of their home farm, Marston, in Zimbabwe, uses a combination of printmaking, digital photography and plain sewing techniques to explore the personal and historical narratives that surround her sense of both displacement and home making. Stitching together memories of the lost homestead, family stories, and understandings drawn from her doctoral studies, McKee creates highly accomplished and engaging works that evoke more than a memorial to the past or a passing nostalgic reverie. Rather she presents ways of reconciling there and then with the here and now. Such conjunctions of space and time can be seen in works like Plication I and Plication II, reverie between two places in which fabric - overlaid with solvent transferred, fragmented images of Marston and Perth - is pleated into a placed tactile intimacy. The plain sewing - a skill learnt from her grandmother - reflects a generational passage of time, while the printed images convey a fleeting familiarity with places lived and experienced.

Considering the affects of living far from her home town Katowice in Poland while undertaking doctoral studies, Monika Lukowska portrays her experiences of place making as she comes to terms with two radically different locations. The combination of lithography and digital technologies provides Lukowska with a perfect vehicle for picturing the particularities of each cityscape, their surface appearances, architectural forms, textures and emotive resonances. Her works not only reveal her deft skills as a printmaker but also highlight her sensitive apprehension of the material conditions of these differing environments. Lukowska's evocation of place can be seen in works like Immersed in coal I, and Nikiszowiec II, where the comfortable familiarity of coal soot that dusts Katowice's cityscape provides a visual leitmotif for rendering her sense of place. In these works, the embodied experiences and memories of over there are collaged into the present realities of now from the viewpoint of here in Perth.

Working together for the first time, McKee and Lukowska bring together a rich and potent understanding of the complex experiences of contemporary nomadic lifestyles, the interplay of memories and everyday realities that are imagined through the sensate material world. In their collaborative work Traversing the Terminus I, II and III the individual artist's concerns for a sensed apprehension of places are brought into dialogue to create a poetics of transition. This panorama of stilled moments in time and space is pleated into a subtlety nuanced meditation, one that transcends nostalgia and sentimentality. Through rendering the light, textures and other aspects of the environmental locale in which they find themselves, these two artists picture a personal and intimate portrayal of this place, as they create a home in the here and now.

In keeping with McKee and Lukowska's contention that places are understood through embodied sensitivities, while we may not be able to smell the soot as it coats Silesia's architecture, nor taste the fruit in the lost orchard left behind, nor hear the sounds of unfamiliar languages as we migrate to new destinations, through the art works in this exhibition we can appreciate those desires and affective experiences that are to be found when travelling through the terminus.

Ann Schilo

September 2016.

References:

Auge, Marc. Non-places: introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity. London: Verso. 1995.

Dr Ann Schilo is a senior lecturer in the School of Design and Art at Curtin University. She is a co-supervisor of the doctoral studies of both Melanie McKee and Monika Lukowska.

A collaboration between Melanie McKee and Monika Lukowska for TERMINUS in search of an (im)possible conclusion

Although the artists have independently explored themes of belonging, place and dislocation, as their paths converge, Perth becomes the terminus where they continue to explore these notions. In this instance the terminus is not perceived as a final destination, but rather as a port, a temporary site of settlement and the point of future departures and arrivals. In light of this proposition, Lukowska and McKee will develop a collaborative artwork to be shown during the exhibition. This artwork will form a critical perspective on the artists' personal experiences, merging their response to dislocation and establishing a conversation between the makers.

2015

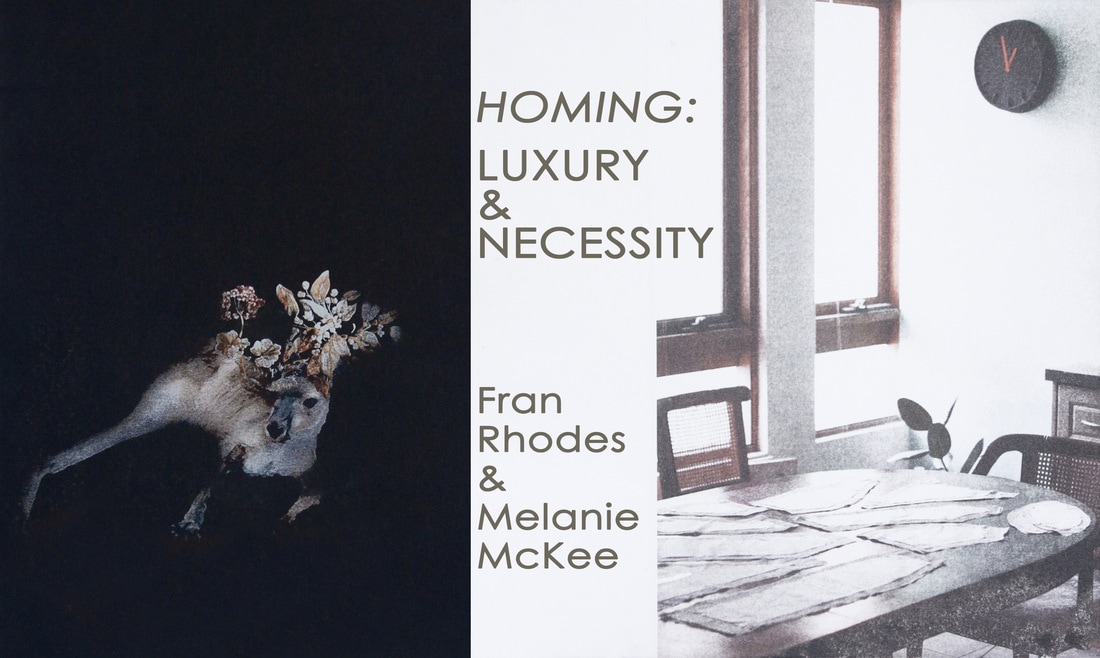

A joint exhibition of recent works by Melanie McKee and Fran Rhodes as part of the Impact9 International Printmaking Conference, hosted by the China Academy of Art, Hangzhou China:

CATALOGUE ESSAY

To be at home in time and place

Graham Mathwin

A common interest in the home, landscape, and material processes link these two bodies of work in Homing: Luxury and Necessity, by Fran Rhodes and Melanie McKee. The use of textile, the focus on its domestic materiality, echoes through each body of work. Yet the manner of addressing place, home, and landscape are different in each. Though both speak from the position of migrants in Australia, Rhodes’ work is an investigation into a new landscape, and the aesthetic paraphernalia she has found there and around it, while McKee’s is an invocation of her grandparent’s farm in Zimbabwe. There is a glimmer of malice present in each work: in the passage of time, and the nature of unfamiliar space. It is contrary to this that each also attempts new acts of homing, to create and recreate the home against the ravages of time, and within the unfamiliar. For the migrant experience indicates the loss of the old, a severing of physical ties. It is in piecing together again, collecting and binding fragments, that the new home is made.

In an attempt to reclaim the feeling of a home, both works invoke intimacy and closeness in their materiality and processes. It is in the intimate nature of the printing of these works, and the intimacy of the garments referenced, and stitching performed. It is particularly present in the embossing in both bodies of work: the pressing of a matrix through paper, to leave an impression – a memory of something physical. It is this kind of indexical and intimate relation that typifies both bodies of work. It is contrary to the possibility of print to be a process that might enable mass production, for the particular processes used here: embossing, sewing, and solvent transfer, are indicative of a deliberate slowness. They are a translation of the digital and photographic age through the action of a press and a hand, through threading and sewing. They are patient attempts to regain time and place through the very physical act of working with your hands.

The broken threads that lie through McKee’s prints are evidence of the process of making, and the attempt to reconstruct, the home. They are fragments that speak of the loss of connection that migration engenders, yet the catching and accumulating of those threads of connection in other places. Although a subsidiary to the garment, the broken threads relate to their creation, and are the traces of making within a place, and perhaps even a making of that place. The images themselves also greet us as fragments, the rubbing of the solvent transfer an attempt to fix an image that invariably erases, and each image displays visions of interstices where threads might gather.

We wear our memories with us, and McKee has taken up her grandmother’s dressmaking practice to reenact this gesture. An act that is compounded through time, that responds to a history and attempts to draw a connection between what was and what is. Acts performed in an old land are printed onto fabric, and embroidered over, to tie the physical presence, the reenactment of a gesture, and the ghosts of memories together. Both are linked in their reclamation of intimacy, yet an intimacy that is still incomplete. Unworn, these fragments of garments are a symbol that is fraying at its edges, images fading into the cloth, their details lost.

There is a similar loss of definition engendered in all the processes used by McKee in her work. The reciprocation of memory with print and photography is well established, often through indexicality, but here there is also the particular approach to the work that has been undertaken: hand-made, faded, discolored, and projected through a half-tone screen or pressed, between the blankets of a press, from one surface to another. The layers of interpretation and manipulation respond to our constant recollection and alteration of our memories, hidden behind the veil of time. This distortion underpins all the work, a translation of things long passed into the contemporary, and things far away into the here, in order to locate them in both.

Rhodes’ work is more concerned with a landscape, a wistful romance can be seen employed to try and draw a memory together with a hope for the new. The ocean and the bush present themselves, complex, dark, and confusing, overlaid with yet more thread, again broken links, but turning towards decorative lace, embroidery and quilt work. The hope and attempt to make again the home where one finds oneself is clear in these works, to draw a thread over the surface of a symbolic landscape, to make clear and define connection, and construct something beautiful there. The harshness of the landscape – or rather, its chaotic construction, is at first reciprocated in loose threads, then overlaid and put in dialogue with the structuring forces and patterns of thread work. The relationship is one of negotiation, as no dialectic operation, no synthesis, is necessarily resultant. It is a gesture towards cohabitation, an attempt to overcome alienation and dissonance through intimacy.

Along with the thread work evident in the prints, the nature of the process of a solvent transfer indicates this intimacy. Yet more than this, it is a transmutation of the photographs that surround us through the action of dissolution, and transference by rubbing and pressing. The very physical nature of the labour brings the work back from the image to something to do with the process of making and remaking. That by an action we might overcome the distances of space and time, or at least construct them into a sensible form, and weave them into our lives.

Both bodies of work are then intimate in their construction, and familiar experiences. There is little closer to us than our memories and our homes, and these works are a testament to the potential to construct and reconstruct them in a floating, uncertain space. They are paper and ink and thread – delicate arts – they are no stone monoliths, but soft tissue, precious and intimate, the record of something easily destroyed, but all the more delightful for it.

September 2015. Graham Mathwin is an artist and writer, currently undertaking Honours studies at Curtin University's School of Design and Art.

《回家,在时空的维度里》

文:格拉哈姆 麦色文

艺术家佛兰罗兹岛和梅勒尼麦基的作品《回家:奢侈和必须》反映了艺术家们对于回家、乡村风景和材质三者的浓厚兴趣。着眼于材质的丰富多样性,纺织的应用在作品里相互呼应。但是对于回家和乡村风景的表述,两位却又不尽相同。尽管她们都是以澳洲移民的身份为创作出发点,罗兹岛的作品通过她自身的审美探究了一个全新的乡村风景,而麦基的作品则是反映了她爷爷奶奶在赞比亚的农场。两件作品表达对时间和陌生环境的恐惧中透露着一丝丝的幽怨。与此同时,两者还在作品中试图去营造一种回家的归属感来抵挡陌生环境里时间流逝的无情。对于移民者来说,背井离乡是一种身心的斩断。因此两位艺术家通过把破碎的细节重新拼凑起来从而重新建立一个崭新的家。

为了再度创作出回家的感觉,两件作品在材质和创作上都蕴藏着一丝人与物的亲密感。尤其体现在作为创作手法的印刷本身就要求人与材质的亲密接触还有服装本身也意味着与身体的亲密接触,更不用说是一针针亲手缝制出来的。具体地说,这种人与物的亲密接触体现在两件作品凸起的压花部分。通过挤压模具压花在纸张上从而留下突起的印记 – 这是一种物理的记忆。这种既有牵引感又有亲密感的制作过程形成了两件作品的特点。在创作过程中采用的具体手法比如压花,缝纫和溶解转印都是有意放慢整个创作过程。而特意放慢制作过程的创作意图再次对印刷这种一般用于大量无差别快速生产的样式形成反比。通过双手穿线和缝纫的身体动作,作品对当代数码和摄影时代起到了另一种诠释。时间和空间的意义也在两位艺术家耐心的肢体劳作中被重新解释。

麦基作品的制作过程和她重构回家的意图通过断头线的应用表现的淋漓尽致。一片片断布头表达移民者与故土剥离的惆怅与此同时重新缝合起来的断布头也反映艺术家在新地方重新聚首的意愿。尽管断头线的应用貌似在整套衣服创作中起辅助作用,但断头线却保留了创作过程的痕迹,甚至被认为就是创作本身。服装表面的图像也体现了分裂意味。运用溶解转印的手法在服装上固定一个半消失的图像,展示多个缝隙被断头线缝合的视觉效果。

我们都随身携带着我们的记忆,麦基借由她奶奶曾经是女装裁缝为创作源头去重新解释这一定义。她的创作纳入了时间的元素,回应历史和试图去搭建过去与现在。她创作中的每一个动作都被深深的印在布料上,之后刺绣的运用加深了物理显现从而再次凸显了她创作中多样的身姿和幽灵般的记忆。两者的紧密联系充分体现她对亲密感的认知和表现,尽管亲密感还未被完全表现出来。这些从未被穿过的断布头变成一个边角正在磨损、图像渐渐消失和细节丢失的象征。

在麦基的创作过程中,定义在被重新解释时有部分缺失。通过溶解转印的手法,记忆中的图像很好地从相片过渡到布料上,但是“这里和那里”也是她作品的着眼点:表现为手工制作、褪色的、脱色的、通过网目铜版曝光或压制的、夹在印刷毡子之间的、从一面到另一面的。解释和手法的多样性和层次感回应了一直以来深藏在时间面纱下我们记忆和回忆的变更。记忆扭曲的体现巩固了她所有的作品,把深藏在过去遥不可及的事件重新翻译进当代,从而可以即在当下又在过去。

罗兹岛的作品更多聚焦于乡村风景,碎片化的记忆被作品中对浪漫情怀的渴望重新连接起来去构建一个新家。作品中的海洋和灌木丛充分体现了自身的复杂、深邃、迷惑、重叠反映了相互交织和断断续续链接的特质,但与此同时也给人装饰性饰带、刺绣和东拼西凑的感觉。罗兹岛想再次创造回家感觉的强烈愿望表现在她利用有序的线条穿越具有象征意义的风景画表面,清晰可见,进而定义链接和构建审美。风景的粗糙混沌一面与脱线的手法相呼应,并和有序线条所构建的张力和图形展开对话。两者的关系是一场不期而遇,因为没有激烈辩证,没有归纳综合,反而是自然的流露和必然的结果。

除了运用有序线条,溶解转印的手法也充分体现了亲密感。溶解转印靠摩擦和按压使相片溶解从而转印的一个转化过程。整个操作过程把一张相片变成反复制作的身体劳作过程。通过身体劳作,我们也许可以克服时空所带来的距离感,或者至少可以赋予时空人性化从而让它渗入我们的生活。

两件作品在思维构建和情感表达上有异曲同工之妙。没有甚么比我们的记忆和对回家的渴望更加触动我们心弦,两件作品再次证明在一个流动和无常的空间里构建和重新构建记忆和回家的无限潜力。作品由纸张、墨水和线条组成 – 堪称精致的艺术作品 – 不是出于整块石料而是柔软的纤,珍贵而亲密,虽易毁坏,却又是它最可爱的一面。

2015年九月。格雷厄姆马思温是一名艺术家和作家,他目前在科廷大学设计与艺术学校就读荣誉学士。

翻译刘鹏刚完成在科廷大学设计与艺术学校博士学位的攻读。

To be at home in time and place

Graham Mathwin

A common interest in the home, landscape, and material processes link these two bodies of work in Homing: Luxury and Necessity, by Fran Rhodes and Melanie McKee. The use of textile, the focus on its domestic materiality, echoes through each body of work. Yet the manner of addressing place, home, and landscape are different in each. Though both speak from the position of migrants in Australia, Rhodes’ work is an investigation into a new landscape, and the aesthetic paraphernalia she has found there and around it, while McKee’s is an invocation of her grandparent’s farm in Zimbabwe. There is a glimmer of malice present in each work: in the passage of time, and the nature of unfamiliar space. It is contrary to this that each also attempts new acts of homing, to create and recreate the home against the ravages of time, and within the unfamiliar. For the migrant experience indicates the loss of the old, a severing of physical ties. It is in piecing together again, collecting and binding fragments, that the new home is made.

In an attempt to reclaim the feeling of a home, both works invoke intimacy and closeness in their materiality and processes. It is in the intimate nature of the printing of these works, and the intimacy of the garments referenced, and stitching performed. It is particularly present in the embossing in both bodies of work: the pressing of a matrix through paper, to leave an impression – a memory of something physical. It is this kind of indexical and intimate relation that typifies both bodies of work. It is contrary to the possibility of print to be a process that might enable mass production, for the particular processes used here: embossing, sewing, and solvent transfer, are indicative of a deliberate slowness. They are a translation of the digital and photographic age through the action of a press and a hand, through threading and sewing. They are patient attempts to regain time and place through the very physical act of working with your hands.

The broken threads that lie through McKee’s prints are evidence of the process of making, and the attempt to reconstruct, the home. They are fragments that speak of the loss of connection that migration engenders, yet the catching and accumulating of those threads of connection in other places. Although a subsidiary to the garment, the broken threads relate to their creation, and are the traces of making within a place, and perhaps even a making of that place. The images themselves also greet us as fragments, the rubbing of the solvent transfer an attempt to fix an image that invariably erases, and each image displays visions of interstices where threads might gather.

We wear our memories with us, and McKee has taken up her grandmother’s dressmaking practice to reenact this gesture. An act that is compounded through time, that responds to a history and attempts to draw a connection between what was and what is. Acts performed in an old land are printed onto fabric, and embroidered over, to tie the physical presence, the reenactment of a gesture, and the ghosts of memories together. Both are linked in their reclamation of intimacy, yet an intimacy that is still incomplete. Unworn, these fragments of garments are a symbol that is fraying at its edges, images fading into the cloth, their details lost.

There is a similar loss of definition engendered in all the processes used by McKee in her work. The reciprocation of memory with print and photography is well established, often through indexicality, but here there is also the particular approach to the work that has been undertaken: hand-made, faded, discolored, and projected through a half-tone screen or pressed, between the blankets of a press, from one surface to another. The layers of interpretation and manipulation respond to our constant recollection and alteration of our memories, hidden behind the veil of time. This distortion underpins all the work, a translation of things long passed into the contemporary, and things far away into the here, in order to locate them in both.

Rhodes’ work is more concerned with a landscape, a wistful romance can be seen employed to try and draw a memory together with a hope for the new. The ocean and the bush present themselves, complex, dark, and confusing, overlaid with yet more thread, again broken links, but turning towards decorative lace, embroidery and quilt work. The hope and attempt to make again the home where one finds oneself is clear in these works, to draw a thread over the surface of a symbolic landscape, to make clear and define connection, and construct something beautiful there. The harshness of the landscape – or rather, its chaotic construction, is at first reciprocated in loose threads, then overlaid and put in dialogue with the structuring forces and patterns of thread work. The relationship is one of negotiation, as no dialectic operation, no synthesis, is necessarily resultant. It is a gesture towards cohabitation, an attempt to overcome alienation and dissonance through intimacy.

Along with the thread work evident in the prints, the nature of the process of a solvent transfer indicates this intimacy. Yet more than this, it is a transmutation of the photographs that surround us through the action of dissolution, and transference by rubbing and pressing. The very physical nature of the labour brings the work back from the image to something to do with the process of making and remaking. That by an action we might overcome the distances of space and time, or at least construct them into a sensible form, and weave them into our lives.

Both bodies of work are then intimate in their construction, and familiar experiences. There is little closer to us than our memories and our homes, and these works are a testament to the potential to construct and reconstruct them in a floating, uncertain space. They are paper and ink and thread – delicate arts – they are no stone monoliths, but soft tissue, precious and intimate, the record of something easily destroyed, but all the more delightful for it.

September 2015. Graham Mathwin is an artist and writer, currently undertaking Honours studies at Curtin University's School of Design and Art.

《回家,在时空的维度里》

文:格拉哈姆 麦色文

艺术家佛兰罗兹岛和梅勒尼麦基的作品《回家:奢侈和必须》反映了艺术家们对于回家、乡村风景和材质三者的浓厚兴趣。着眼于材质的丰富多样性,纺织的应用在作品里相互呼应。但是对于回家和乡村风景的表述,两位却又不尽相同。尽管她们都是以澳洲移民的身份为创作出发点,罗兹岛的作品通过她自身的审美探究了一个全新的乡村风景,而麦基的作品则是反映了她爷爷奶奶在赞比亚的农场。两件作品表达对时间和陌生环境的恐惧中透露着一丝丝的幽怨。与此同时,两者还在作品中试图去营造一种回家的归属感来抵挡陌生环境里时间流逝的无情。对于移民者来说,背井离乡是一种身心的斩断。因此两位艺术家通过把破碎的细节重新拼凑起来从而重新建立一个崭新的家。

为了再度创作出回家的感觉,两件作品在材质和创作上都蕴藏着一丝人与物的亲密感。尤其体现在作为创作手法的印刷本身就要求人与材质的亲密接触还有服装本身也意味着与身体的亲密接触,更不用说是一针针亲手缝制出来的。具体地说,这种人与物的亲密接触体现在两件作品凸起的压花部分。通过挤压模具压花在纸张上从而留下突起的印记 – 这是一种物理的记忆。这种既有牵引感又有亲密感的制作过程形成了两件作品的特点。在创作过程中采用的具体手法比如压花,缝纫和溶解转印都是有意放慢整个创作过程。而特意放慢制作过程的创作意图再次对印刷这种一般用于大量无差别快速生产的样式形成反比。通过双手穿线和缝纫的身体动作,作品对当代数码和摄影时代起到了另一种诠释。时间和空间的意义也在两位艺术家耐心的肢体劳作中被重新解释。

麦基作品的制作过程和她重构回家的意图通过断头线的应用表现的淋漓尽致。一片片断布头表达移民者与故土剥离的惆怅与此同时重新缝合起来的断布头也反映艺术家在新地方重新聚首的意愿。尽管断头线的应用貌似在整套衣服创作中起辅助作用,但断头线却保留了创作过程的痕迹,甚至被认为就是创作本身。服装表面的图像也体现了分裂意味。运用溶解转印的手法在服装上固定一个半消失的图像,展示多个缝隙被断头线缝合的视觉效果。

我们都随身携带着我们的记忆,麦基借由她奶奶曾经是女装裁缝为创作源头去重新解释这一定义。她的创作纳入了时间的元素,回应历史和试图去搭建过去与现在。她创作中的每一个动作都被深深的印在布料上,之后刺绣的运用加深了物理显现从而再次凸显了她创作中多样的身姿和幽灵般的记忆。两者的紧密联系充分体现她对亲密感的认知和表现,尽管亲密感还未被完全表现出来。这些从未被穿过的断布头变成一个边角正在磨损、图像渐渐消失和细节丢失的象征。

在麦基的创作过程中,定义在被重新解释时有部分缺失。通过溶解转印的手法,记忆中的图像很好地从相片过渡到布料上,但是“这里和那里”也是她作品的着眼点:表现为手工制作、褪色的、脱色的、通过网目铜版曝光或压制的、夹在印刷毡子之间的、从一面到另一面的。解释和手法的多样性和层次感回应了一直以来深藏在时间面纱下我们记忆和回忆的变更。记忆扭曲的体现巩固了她所有的作品,把深藏在过去遥不可及的事件重新翻译进当代,从而可以即在当下又在过去。

罗兹岛的作品更多聚焦于乡村风景,碎片化的记忆被作品中对浪漫情怀的渴望重新连接起来去构建一个新家。作品中的海洋和灌木丛充分体现了自身的复杂、深邃、迷惑、重叠反映了相互交织和断断续续链接的特质,但与此同时也给人装饰性饰带、刺绣和东拼西凑的感觉。罗兹岛想再次创造回家感觉的强烈愿望表现在她利用有序的线条穿越具有象征意义的风景画表面,清晰可见,进而定义链接和构建审美。风景的粗糙混沌一面与脱线的手法相呼应,并和有序线条所构建的张力和图形展开对话。两者的关系是一场不期而遇,因为没有激烈辩证,没有归纳综合,反而是自然的流露和必然的结果。

除了运用有序线条,溶解转印的手法也充分体现了亲密感。溶解转印靠摩擦和按压使相片溶解从而转印的一个转化过程。整个操作过程把一张相片变成反复制作的身体劳作过程。通过身体劳作,我们也许可以克服时空所带来的距离感,或者至少可以赋予时空人性化从而让它渗入我们的生活。

两件作品在思维构建和情感表达上有异曲同工之妙。没有甚么比我们的记忆和对回家的渴望更加触动我们心弦,两件作品再次证明在一个流动和无常的空间里构建和重新构建记忆和回家的无限潜力。作品由纸张、墨水和线条组成 – 堪称精致的艺术作品 – 不是出于整块石料而是柔软的纤,珍贵而亲密,虽易毁坏,却又是它最可爱的一面。

2015年九月。格雷厄姆马思温是一名艺术家和作家,他目前在科廷大学设计与艺术学校就读荣誉学士。

翻译刘鹏刚完成在科廷大学设计与艺术学校博士学位的攻读。